Giannoulis Halepas: The tragic life of the greatest Greek sculptor

As you disembark at the port of Tinos, one of the first images you see are the huge banners with the image of Giannoulis Halepas. It has been 81 years since his death and in this magical place, the personality of the leading artist dominates. Especially in Pyrgos, the most beautiful settlement of Tinos and the birthplace of this genius artist where, despite the difficulties he faced in the course of his life, he managed to give a unique form to white marble.

The Tower is considered the center of modern Greek sculpture. Walking on its picturesque cobbled streets, you meet everywhere the signs of art and artistic creation or expression. Around you, the basic materials, stone, wood, marble, and clay.

Giannoulis Halepas was born on August 24, 1851, and grew up in an environment of dust, marble, and clay. John’s father was one of the island’s greatest craftsmen, a successful professional with intense business activity in the Aegean, Izmir, and the coasts of Central Asia, Mount Athos, Bucharest, Syros, Athens, and Piraeus. The incessant sound of hammers and mantras must have significantly affected Giannoulis, the first of five children in the family.

From a very young age, he stood out from the other children, while his toys were unusual. He was sensitive, sensitive, and eccentric. He grew up among shapes and forms, low walls, and the dusty environment – inside the ancestral workshop, he realized that he was a born sculptor.

His mother Irene, the genus Lampaditis, was an imposing, strict, taciturn, and oppressive mother. She loved her eldest son more than any of her other children, but she was also the one who had a strong influence on him.

As Christos Samouilidis writes in a fascinating and complete biography entitled “Giannoulis Halepas – The tragic life of the great artist” published by Estia, “seven spring dusk the seven-year-old Giannoulis did not return home. He secretly entered his father’s workshop and sat in a corner, invisible, to watch him at work. But suddenly his mother appeared in front of the door. Mrs. Rini violently pulled him towards the house and then immediately started beating him mercilessly. Giannoulis cried out in pain and tried to escape again, but his mother held him tightly by the hand and continued to beat him. “

Punishment, fear, and threats led him to deny his love for her. The tenderness of the mother-child relationship had turned into hatred. His mother was determined not to let her son become a marble. He had other ambitions for Giannoulis, he considered his work marble inferior.

During his school years, his performance in the lessons was excellent and he had started to develop his skills. For a long time, he did not return to his father’s workshop but continued to go to other workshops in the village.

In the summers the sea was what fascinated him, the games on the beach of Panormos, the baths, and the dives on the rocks. Another of his favorite habits was walking with his friends in the orchards of Lagada.

Later, in 1869, the whole family went to Athens for Giannoulis to attend sculpture classes at the Polytechnic. It was the time when he woke up in the morning full of dreams, desires, and hopes. It was a period when he was looking forward to finding expression in his talent and developing his passion for creation. His teacher was the Greek-Bavarian Leonidas Drossis. He graduated with honors in 1872. He was only twenty-one years old.

A year later, in 1873, with a scholarship from the Evangelistria Foundation of Tinos, he went to Munich, where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts. At that time, the classicism of ancient Greece prevailed in art. His teacher was the famous sculptor Max von Widmann. During his stay in Munich, he did not have significant love or many friendships, apart from meeting one of his classmates, George Konstantinidis. His only love was Marigo Christodoulou.

n Munich he exhibited his works “The Tale of the Beautiful” and “The Satyr Who Plays with Love”, for which he was awarded the Gold Medal. The “Satyr who plays with Eros” was presented together with the relief of “Philostorgia” in an exhibition in Zappeion, Athens.

The reception he received was inexplicably negative. As Christos Samouilidis notes in his book, this was the fourth time that Giannoulis Halepas was wounded by his homeland. The first was when his scholarship was cut in half, the second when he was delayed for a year and the third when it was stopped. For this reason, at the beginning of the spring of 1876, he returned to Athens and opened his own laboratory.

It was not long before he visited his village thinking that there he would meet his beloved and fellow villager Marigo. His love for her had remained unquenchable, despite the distance. Her figure was always present in his mind.

Shortly before his return to Athens, she decided to go to Christodoulou’s house to ask for her hand. He was denied it and this rejection determined his life. In his personal diary as an insurmountable wound. This unfulfilled love would mark the beginning of its collapse.

In January 1878, a woman in black visited him in his workshop in Athens. She was the mother of Sofia Afentaki who had passed away at the age of 18 from tuberculosis. This woman asked Giannoulis Halepas for a burial monument with the statue of her daughter. This masterpiece of modern Greek sculpture was recorded as his top work. It remains unsurpassed, in the First Cemetery of Athens.

This work aroused the envy of his peers. The triumph of “Sleeping” was covered by absolute silence. “This insidious prolonged calm around him turned his mind upside down. He killed him “writes Christos Samouilidis.

The first symptoms of his mental shock had begun to appear. Each of his works destroyed it. His condition did not improve, so, after ten years, he returned to Tinos. An intermediate trip to Italy was not able to help him. Short walks in the village, in the high mountains, in the hidden coves and the endless agnanti in the sea monopolized his daily life on the Cycladic island

In 1888, after several crises and suicide attempts, the sculptor was admitted to the Corfu Hospice as “suffering from dementia”. Empty days, fruitless hours, and useless weeks. His gaze was constantly flat and melancholy. His thought is motionless and his world is surrounded by vast darkness. His monotony was broken by a letter from his mother, in which he informed him that his father had died. When he read it, he cried for a long time.

No one close to him, except his old friend George Konstantinidis, ever visited him in the outdated Corfen Hell Hospital. The reasons for his incarceration included: “From the pointless laugh, the fears, the aggression against his father and his relatives, the suicide attempts”. It was noted that: “They suffered from dreams, the consequence of which was the masturbation of a failed love”.

He remained there for 13 years, 10 months, and 27 days, until June 6, 1902, when his mother received him as “quiet”. She still considered sculpture to be to blame for her son’s illness and therefore disbanded any of his creations. Upon his departure and return to Pyrgos, Giannoulis Halepas was for his fellow villagers the “madman of the village”. He turned to animal grazing and agricultural work. He became an eerie figure, a shadow of himself. He was now cut off from the art he loved, sculpture.

As soon as the professor of the Polytechnic, Thomas Thomopoulos, learned that Giannoulis had left the insane asylum, he visited him in Tinos and was shocked by the situation he saw. The great poet Kostis Palamas, in 1915, in the newspaper “Empros”, will write about Halepas that “the light of art ceased to illuminate his street” and “he was left alive” to “graze goats” in his birthplace.

Indeed, this hierarchical form of sculpture lived in poverty, grazing sheep and bearing the heavy stigma of the crazy village. The next year his mother died suddenly, while she had already mourned the death of her two children, Katerina and Praxitelis.

Next to his mother’s body, Giannoulis stood indifferently, subduedly, and with apathy. At one point, while he was missing, he was found in the basement, where he had begun to shape the clay. He is said to have said to his mourning nieces: “Shut up and I will catch the art of working.” He felt free now. Of course, his breakup had come at a later date.

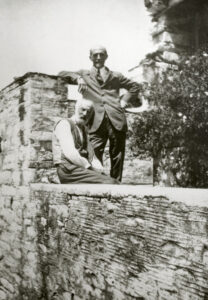

Early the following year he felt confident enough to start a new, lonely life at his home in Pyrgos. Thomas Thomopoulos copied many of his works in 1923 and presented them after two years at the Academy of Athens. From this exhibition in 1927 Halepas was awarded the Excellence in Arts. At the age of 76, the great artist will be publicly recognized and will be accepted by the intellectual world. “Everything comes late,” he will say to himself, no longer able to enjoy glory and happiness.

In 1930, Irini Halepa’s niece urges him to settle in her house, in Naples, at 35 Dafnomili Street. The genius sculptor will be in Athens where he will work intensively. Favorite themes that he repeats are “Medea”, “Satyr and Eros” and “Fairy Tale of the Beautiful”. He was now a recognized figure in the arts.

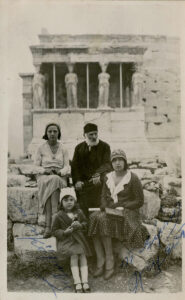

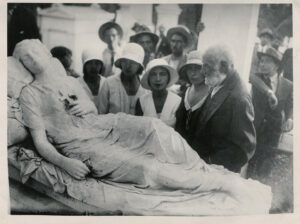

On August 27, 1930, he decided to visit his “Sleeping Beauty”. An unexpected crowd from all over Athens created the inseparable at the entrance and in the courtyard of the First Cemetery, at such a point that the police had to intervene for the artist to go to the spot. Fifty-two years after its creation, Halepas would meet his legendary work. The emotion was great and his inner turmoil was evident

When they returned home from the cemetery, his niece asked him if the rumors were true that he loved Sofia Afentaki. He then replied that he only loved Marigo. A pure and deep romance. Eventually, she married someone else – her father and some relatives played a key role in that.

He stayed at Dafnomili 35 for the last eight years of his life. His hands began to tremble, and old age and fatigue were evident. Hemiplegia killed his right arm. On September 15, 1938, Giannoulis Halepas will leave his last breath, having his loved ones by his side.

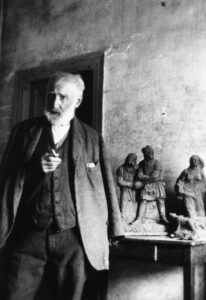

In total, his works that survive to date are estimated at about 150, which include sculptures and many drawings and sketches.

This ascetic figure was the symbol of the power of talent but also of the tragic loneliness of the irreconcilable artist. He experienced rejection, frustration, derogatory looks, devaluation, and marginalization. When he finally experienced the glory, the pan-Hellenic recognition, and the universally recognized appreciation, it was too late.

Today, in Pyrgos, in every corner of the house museum, the spirit of the genius sculptor dominates, who for a lifetime shaped and sculpted. His clay always wanted to take a soul. The invisible mysteries of existence and human passions were the main components of his inspiration, while Greek mythology was the main tool of this genius.

Hard trials, erotic frustration, adverse social environment, psychopathy, artistic inactivity, envy, conflicts with family and society. Nevertheless, the name of this man is inscribed among the greatest names in the history of art.

At Pyrgos’s house, the presence of Giannoulis Halepas remains strong: the hanging clothes, handwritten notes, family photos, household utensils, his personal belongings, his bedroom, and workshop are reminiscent of the novel life of the leading Greek sculptor and pioneer European modernism.

I took the road to neighbor Panormos. My thoughts were still dominated by the fascinating course of this special and mythical case. The Tinian landscape with its steep peaks and bare rocks, the lush spring slopes, and the stepped fields, the terraces, and nature confirm that Giannoulis Halepas is the poet of the chisel and our national sculptor.

A legend who dedicated his whole life to the art of sculpture.