The Art World Ignored Faith Ringgold for Decades.

The art world has as much to do with access as it does with art. So a big part of the artist Faith Ringgold’s retrospective at the New Museum in New York, a sweeping survey spanning almost six decades, is organized around the fact that she didn’t have a lot of inroads. Looking back, her practice even flourished in spite of it.

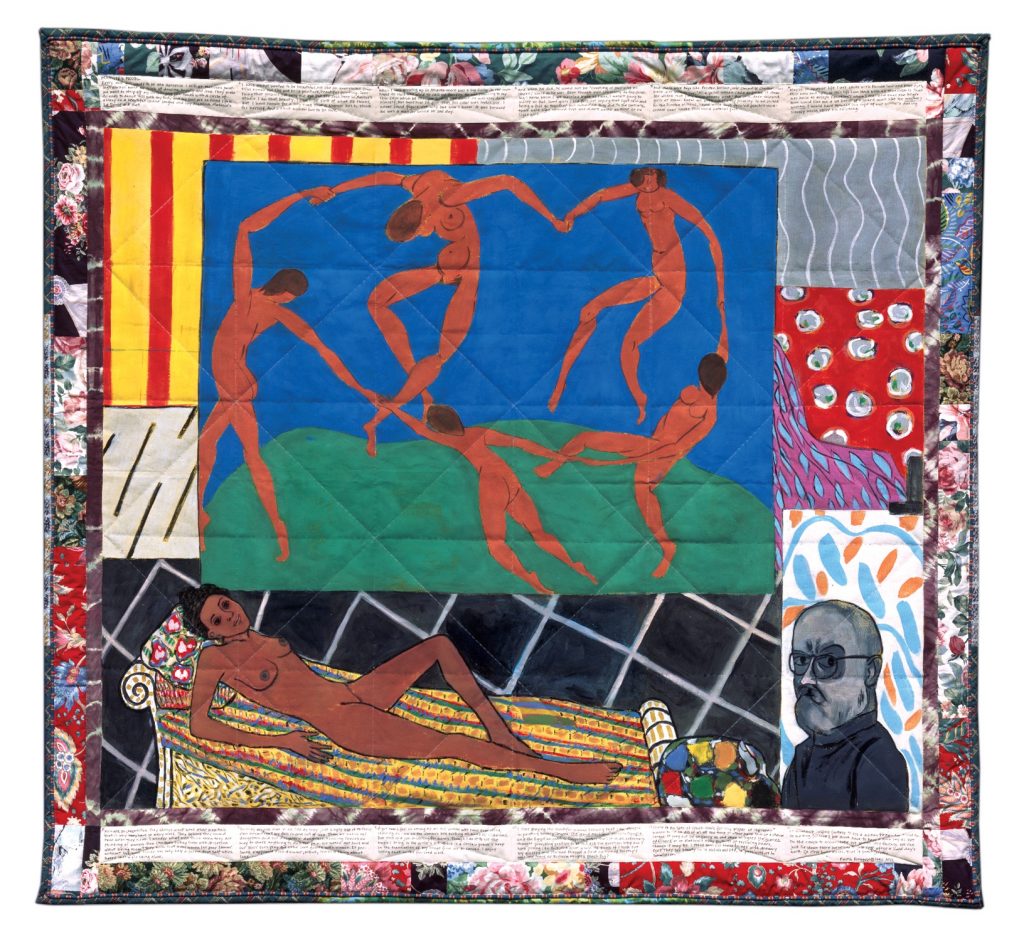

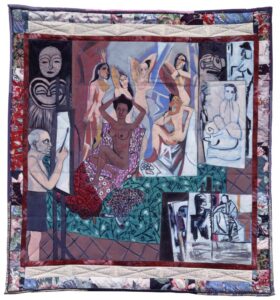

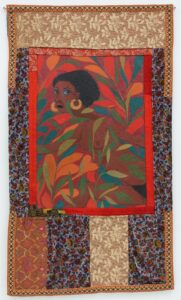

This is because Ringgold never lost sight of who she was making work for. Her pieces are “very much coming from a Black womanist perspective, as opposed to a reactionary viewpoint,” artist Tschabalala Self, who first saw Ringgold’s work as a child in Harlem, told Artnet News. “Her works strongly exist within this aesthetic of Black American storytelling, and for the edification of that community, not from a didactic place of making work or explaining Black life to a non-Black audience.”

Ringgold’s retrospective is the first major New York museum show of her work since 1998 when the New Museum also presented her work. Another show was held at the studio museum in 1984.

“The gaps between the first two retrospectives immediately give you a sense of the reception and of the marginalization of her work,” Massimiliano Gioni, the current show’s co-curator, told Artnet News. But her art “always found new ways to exist in spite of the many complicated conditions she was in.”

In the end, those complicated conditions are hard for anyone to ignore—even curators putting together a show about Ringgold’s life and work. In the years since her 1998 retrospective, Ringgold, now 91, was so alienated from the mainstream art world that she was forced to develop a practice that could exist and thrive outside it.

In her 1995 memoir, We Flew Over the Bridge, Ringgold reveals how, in the ‘70s, her career “started with a bang and ended with a whimper.”

After launching her “American People” series in the ‘60s hyper-realist paintings that zeroed in on the racial and gender strife characterizing Ringgold’s everyday life at a time when the art world was obsessed with work that was “cool, unemotional, uninvolved, and not ‘about’ anything,” as she wrote she joined the stable at Spectrum Gallery on 57th Street, becoming the only Black artist represented there.

During her tenure, she pivoted to her “Black Light” series, a group of pieces that included agitprop-style texts and African-inspired portraits with even more overt Black Power messaging, to the point where she eliminated the use of white paint altogether. By 1970, she’d landed her second solo show at the gallery, still eager to see what the art world could ultimately do for her.

By the end of the decade, she found her answer: not much.

Feeling disheartened, Ringgold forged ahead, finding new opportunities. But even now, as the art world turns its eyes to her work, many audiences still don’t know that she’s much more than a painter. For one, she was also a prolific sculptor.

On top of her teaching career, she conducted lectures and put on performances at colleges and universities, producing doll-like soft sculptures as props. These life-sized, often heavily adorned works also provided Ringgold with a way of capturing a small piece of the world that she was able to call her own.

“She created a whole system of support for herself that was not the traditional gallery [system] in New York,” Gioni said.